FUNCTIONS OF THE TRUST COMPANY IN THE FIELD OF LAW.

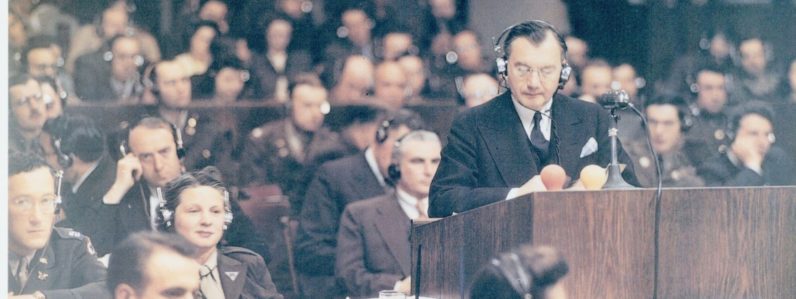

By ROBERT H. JACKSON, JAMESTOWN, N. Y.

What has happened to those whom Woodrow Wilson called the ''dwindling body of general practitioners, who used to be our statesmen? A generation ago a lawyer was identified with the family fortunes, counseled the indiscreet youth, approved title to the new home that came with manhood; drew the articles of co-partnership or incorporation when a shop or store was acquired, collected the business accounts, drew the Will, handled settlement of the estate and then started over the same road with another generation.

To-day the defense of speeding youth falls to the insurance company, a title guaranty company passes title to the new home, a Charter Company incorporates the shop, credit insurance companies and collection agencies collect the accounts and a trust company handles the estate. The family lawyer, like the family doctor, has gone the way of the family horse.

Compared with the lawyer, the Trust Company is a new institution in the legal. It began business with but a vague definition of its functions, guided only by a sense of

profits, and found itself frequently, and perhaps often unintentionally engaging in some branches of law practice. As banking has tended to become a profession, recognizing a

gradually shaping code of ethics, fostered by state and national associations which parallel in purposes our own, the era of friction and mal-adjustment between bank and Bar seems to be generally passing. No more does the eastern Trust Company advertise “Come in and have your Will drawn free of charge." No longer do lawyers and the banks try to discredit each other, as happened on a state-wide scale in the west.

The relations and functions of bank and Bar are being shaped for the better interests of the whole economic and social order rather than for the narrow interests of either group. If we consider only selfish interests, it is doubtful if the Bar should complain of layman law practice. The litigations that have come to the profession from the law work of bankers, justices of the peace, notaries and real estate men have been numerous and profitable. The more far-sighted leaders of the banking profession insist that the Trust Department shall not practice law. They regard the good will of the Bar as an asset, but beyond this they recognize that the legal profession, requiring careful preparation and high standards for admission, subject to strict and summary discipline, and occupying a confidential and privileged relation to the client and an official relation to the court, is not a proper field for a banking corporation. The lawyer must forego means of promoting his business freely conceded to the banker. What business man or banker would wish his own counsel to publish a statement of his assets and liabilities, list of cases won, letters of recommendation, and employ on a percentage basis solicitors of new accounts? It may be good business for the trader to stimulate by advertising public desire for unnecessary products. But the lawyer must, in Doctor Johnson's

language, "direct the doubtful and instruct the ignorant," "prevent wrongs and terminate contentions" even at the cost of preventing or terminating his own employment.

That we fail to attain this ideal does not justify invasion of the legal field. Instead, the influence of the business community, the "power of the retainer" if used to advance ethical and discourage unethical lawyers is more effective than court discipline. It fails only because a substantial part of the business community wants lawyers of doubtful ethics to perform its doubtful tasks.

The bar does not maintain public confidence as well as the bankers, because we are slower to get rid of our offenders. Let the young banker be even suspected of doubtful reliability and the self-interest of the institution prompts his quiet discharge. Lack of recommendation prevents re-employment elsewhere. He is out of his profession for his profession's good. But the offending lawyer can only be disbarred upon legal evidence, some other lawyer must prepare and publicly present it, and since usually he has no personal wrong to redress, the reward of the prosecutor is to be labeled a busybody. Hence, merely to be identified with banking is evidence of responsibility, character and ability that has stood careful selection and is safeguarded by constant oversight. The public accepts neither our tests of admission nor our legalistic method of discipline as equivalent safeguards and prefers to place its faith in the Banker. Must we not acknowledge that mere membership at the Bar does not carry a guarantee either of

character or of ability and that while our best members aim at a higher professional ideal, the banker wins by a more uniform fidelity to a more common ideal? Our weakness is more obvious than an effective remedy.

The office of the lawyer, however poorly filled, is too delicate, personal and confidential to be occupied by a corporation. Court of Appeals declares that "A Corporation can neither practice law itself nor hire lawyers to carry on the business of

practicing law for it."

Matter Co-operative Law Co., 198 N. Y., 479.

Penal Law, Section 280.

This applies to Trust Companies, collection agencies, title companies, insurance companies and all others whose activities lie close to law practice. Since a corporation can have no learning, pass no mental test, and its character, if any, may change as its stock control changes, the corporation obviously cannot become a lawyer. And if a corporation employ a lawyer, either as trust officer or what not, a relation of master

and servant is created. The lawyer that a corporation would rent out to others would still be its servant, owing his first duty to the corporation employer. The relation of lawyer and client does not admit of any middle man or brokerage.

Trust Companies of New York State, with few stubborn exceptions, recognize the sound public policy prohibiting corporate law practice. In the metropolitan area, owing much to the guidance of Mr. Julius Henry Cohen, representing the New York County Lawyers' Association, the lawyers and bankers seem to have arrived at an inter-professional- code that prevents friction and complaint. In Buffalo the Trust Companies are leading contributors to the Bar Association's new headquarters and in Jamestown our Bar Association has concluded an agreement with the banks defining the functions of each. The New York City Association of Trust Companies has published a report to its members making a full statement of the viewpoint of the Bar and recommending

''That members of this association disclaim any desire or purpose to, draw wills or other legal documents for customers, or to furnish their own counsel for that purpose, or to give any legal advice, but on the contrary that they expressly recommend to inquiring clients that they shall have their wills and other legal documents prepared by their own lawyers".

* * * * * * *

" That without in any way impairing their discretion,

the members of this Association encourage the practice of

retaining the counsel of the testator or donor as counsel

for the executor to the lawyer, as well as in its advantage in the adminis-

tration of the trust estate ".

Through the agencies of Bar associations and bankers associations, the more thoughtful lawyers and bankers are advocating much the same relationship of parallel functions and interdependence. To bring individual institutions to a good faith application of these principles is the remaining problem.

What shall be done with the trust department that disregards the best sentiment of both Bar and bankers and persists in practicing law?

First, Criminal proceedings have been invoked with success where a Trust Company advertised to advise concerning wills and called its own attorney who drew the will without charge and named the bank executor.

People v. Peoples Trust Co., 180. A. D., 484.

Secondly, there is an effective remedy in the proceeding to vacate and annul the charter of a corporation exercising a privilege or franchise not conferred by law (General Corporation Law, 131-C. P. Act 1217). As practice of law is strictly prohibited to a corporation (Penal Law, 280) to do so with some degree of continuity would subject the offender to forfeiture of its corporate being. As the mere application by men of standing and responsibility to commence such a proceeding might be serious to a bank, it should only be invoked in a dear case, and in a clear case persisted in, it should be resorted to without reluctance and prosecuted without quarter. This State Association should promptly come to the aid of a local association where facts warrant such a proceeding.

Thirdly, there are possible legislative remedies. Missouri provided that the appointment of a corporate executor or trustee may be revoked where the will is drawn by one in its

employ. Many testators are influenced by the persuasive advertising of those interested in the creation of trust business, and figures of insurance statisticians as to the rapid dissolution of estates, which never remind us that the average insurance estate is under $10,000, is provided to meet necessities, and its disappearance may indicate otherwise use as well occasional squandering. If small estates are to be tied up with no power to invade principal even in extreme need, it should be only with advice of counsel not interested in perpetuating the trust, and the Missouri Statute has much to recommend it.

Fourth, There is authority that a corporation which assumes to act as an attorney without license is in contempt of court, punishable summarily and subject to injunctive process. The Chicago and the Illinois Bar Associations have invoked this drastic remedy against the Peoples Stock Yards Bank which has been found by the Special Master to have engaged in a fairly general practice of law through attorneys in its employ. Keeping the fees for itself and acting in the name of its attorney employees, conducted in court about 200 probate proceedings a year, seven or eight foreclosure proceedings a month, and drew 150 to 200 wills a year, free if the bank was named as executor and for from $5 to $25 each if it were not, handled large number of real estate transactions, leases, trust deeds and title opinions. The bank refused to produce its books but counsel compute from the testimony probable fees of over $150,000 per year. The Illinois Bar Association in 1926 notified the bank of its violation of the law. It then organized a purported law firm using the names of three young lawyers in its employ, paying them fixed salaries, and continued all of the foregoing practices under their firm name, retaining for itself the fees. The master has found that similar practices are frequent in Illinois.

The Bar Associations contend that for a bank to represent itself as entitled to practice law without a license from the Supreme Court is a contempt of that Court, and ask punishment and injunction.

The Referee has upheld the Association and the Bank's appeal is pending in the Supreme Court.

In seeking any remedy; however, we meet the difficult question "What is practice of law and what is not?" Just what is it we do not want trust companies to do? When we consider illegal practice, whether by trust company, collection agency, real estate office, a city notary public or a rural justice of the peace, the first problem is to define the proper limits of our own as well as of the other man's business. The members of

our profession in the legislature and courts should set up clear cut boundaries if we are to punish trespassers.

The Court of Appeals has failed to render even crude first aid. At the same term of court it considered two cases, in each wrote three opinions, in each divided four to three and

in each came to exactly the opposite conclusion from the Appellate Division. The net-result was that it held one layman who for a fee drew a contract of sale and a chattel mortgage guilty, and another who for a fee completed a chattel mortgage blank not guilty, and took pains to state that it had merely settled the status of the act involved in the indictment.

People V. Title Guarantee & Trust Co., 227 N.Y. 366.

People v. Alfani, 227 N. ~· 344.

If a court of such eminence and learning in two efforts merely adds to that "wilderness of single instances " which makes "the lawless science of our law," it is apparent that any layman may transgress the disputed boundary with best of intent and effort of a mere lawyer to eliminate the zone of twilight, must be sheer presumption. Acknowledging

it to be such, I will try to uncover some of the old monuments if not to set new ones.

It seems axiomatic that a monopoly protected by law, such as our right to practice, can only be justified and maintained as to work which requires strict professional qualifications and which is not in its nature clerical or administration. Outside of strictly professional fields lawyers subject themselves to the ordinary laws of free competition.

The Bar in America has taken unto itself a field much broader than that claimed in any other country, institutions of which are comparable. We attempt to be in one office barrister, solicitor, corporation executive, notary, scrivener, auditor, tax clerk, title examiner, process server investigator, and in smaller towns we find insurance, brokerage of mortgages, writing surety bonds, real estate and rental collections

combined with the law.

In my own city lawyers demand that real estate men shall not draw conveyances, yet law offices collect rents and manage real property. We demand that accountants shall not advise as to legal rights but that lawyers shall prepare accountings. The Bar insists that bankers must not draw the client's will- but many lawyers recommend and even sell investments in which they are not always disinterested and these extra-professional activities of lawyers have brought as much disaster to my community as has ever come from the law practice of laymen. It is all very well to claim that our field is protected

by monopoly while the other man's is but commons on which all have equal rights. But my rural experience leaves a strong impression that a fence not strong enough to keep your own herd in will not keep your neighbor's herd out. And, next to cleaning our professional house to win public confidence, the most important step in preventing encroachment upon our practice is to surround it with a line we are willing ourselves to respect and to stay in our profess1onal places.

In France a lawyer may not engage in any other occupation, and may not be a salaried employee or even a public officer and retain his place at the Bar. In Italy there are similar restrictions. In England the work of the barrister is closely circumscribed by tradition and no fee would tempt him to do clerical chores that are not within the strict boundaries of his profession. It is hard to escape the conclusion that the American lawyer has been the first to breakdown the traditional boundaries of his ancient guild and has not yet built up a tradition to restrain the "jack-of-all-trades" tendency.

I am reluctant to advocate specialization. I like the contemptuous definition of a specialist as "one who learns more and more about less and less." Yet it seems about time that we cease trying to be all things to all men and determine what functions shall be distinguishing and exclusively professional ones, protected by monopoly, and what we should for the good of society and ourselves relinquish to the "open shop."

There are many quasi-legal jobs that are clerkship chores and how can it ultimately matter greatly whether that clerk be employed by a bank or a law office. Anything that can properly be done by a clerk, lawyers have no right to do under rates adjusted to professional work. If law offices are to do all manner of clerical business they must organize for it. For the good of the profession I should prefer that the quasi-legal

business go to the banks rather than that banking organizations come into the law offices. Too many lawyers are now merely executive managers of a staff of clerks of varying qualifications and duties. We must confine ourselves to our art, which is individual, and is incapable, except in limited degree, of delegation, and which is a matter of personal skill, character, experience and talent, and is not subject to mass

production methods.

The question now is whether the Bar is not trying to maintain a legal monopoly of a field larger than can be fully and efficiently occupied by men of one standard of education and one code of ethics. No one man can begin to cover the present field of legal practice, and we are compelled to practice by aggregations of specialists, scarcely discernible in lack of personality from· a corporation. It complicates our educational

problem to stretch a single standard of admission to cover all

members of the group from the managing clerk to counsel appearing in the highest appellate courts.

Moreover our functions and interests are too divergent to make a cohesive, effective and influential Bar. The bankers form a compact self-confident guild of uniform interests, who know just what they want and unite in getting it. But we lack such influence in our collective capacity, because we have no economic solidarity. When unprofessional methods of obtaining business are mentioned, trust company lawyers mean the bankruptcy ring, the bankruptcy lawyer means the ambulance chaser, the ambulance chaser points at the lawyer whose retainers are sent him by the trust company. In every wrong, every evil practice, every defeat of administration some numerically powerful group of lawyers claims a vested interest, a few indicate concern and the mass are indifferent to both. Thus is our house so big and its interests so diverse that it is

always a house divided against itself.

Where, then, shall we set our stakes against the Trust Company?

The line established by law was so vague that our Jamestown Bar named a committee to agree with the banks upon a practical line of demarcation right to do tasks requiring legal skill and learning and still give the public the fullest efficiency from corporate fiduciary service. Our advances were met by a communication signed by every Trust institution in the city, largely the work of Walter H. Edson, one of those trust officers who are advancing trust service to a high professional plane, and I offer it, not as a solution so much as evidence of its difficulty, and as indicating a method by which this association and the bankers might well proceed to formulate an inter-professional code of ethics instead of leaving our difficulties to solution by occasional and sterile litigation is addressed to the Bar association committee, is signed by the banks and follows :

"The trust officers of all the Jamestown Banks that have trust departments desire to submit the following as confirmatory of, and supplementary to, the discussion had at their recent conference with your committee:

The banks and trust companies of Jamestown, their trust departments and officers are unanimous in their desire to comply not only with the letter but also with the spirit of the statutes that prohibit practice of law by corporations or other unauthorized persons. Among the officers of Jamestown banks are a number of lawyers none of whom are now engaged in general practice of the law-their entire time being taken up with the performance of services to their respective banks. Among such services are, the giving of legal advice to the banks in all their departments and the preparation and approval of

legal papers to which such banks are parties. In case it seemed desirable these lawyers would doubtless feel at liberty to appear in court as attorneys representing their

respective banks and to perform any other legal service that might be required of them on behalf of the banks who are their clients. As individuals they still possess and upon occasion reserve the right to act as attorneys at law representing such interests as may be entrusted to their care, owing the same duties and obligations and exercising the same rights and powers while so doing as other lawyers-the compensation for their services in such matters to be their personal reward and in no way to inure to the benefit of the banks they represent.

The fact that certain officers of our banks are known to be attorneys who have formerly been engaged in general practice has a tendency to cause the public to believe that the banks where they are located can be called upon for legal services or at least for legal advice. In spite of painstaking efforts on the part of the banks to remove such impression, individuals frequently seek to obtain such legal assistance from the banks, sometimes in the expectation-Of paying for it but more often in the hope of obtaining it for nothing. The banks and the attorneys associated with them are glad to join with the Bar Association in every effort to prevent unlawful practice of the law and to make clear the real nature of the service that can be lawfully rendered by banks and their trust departments. They desire to maintain the highest standards of legal ethics and business propriety in all the affairs with which they deal. Many such matters present difficult questions of mixed law and business. It is not always easy to determine just where the boundary line lies between business and the practice of the law. We shall be glad to do everything in our power to make that line clear and to exclude from possibility the unlawful practice of the law by banks or trust companies of the City of Jamestown.

The following are some of the difficult questions that arise in connection with the subject:

1. A lawyer-officer often finds it necessary to draft documents and negotiate transactions with other persons who are not represented by, or acting under the advice, of an attorney. The power; and the property of his doing so, can hardly be questioned if the honesty and fairness of what he does is not otherwise open to objection. He

represents the bank and is not in a position to act as counsel for other parties to the transaction. Whatever he does will be subject to scrutiny and the strict rules of

construction that apply in such cases.

Under no circumstances would the lawyer-officer seem to be authorized to prepare or supervise the execution of wills. A will is not a .contract to which the bank could be a party. Trust Agreements between individuals and a bank or trust department seem to be in a different category but the drafting of such agreements where they involve important rights should be subject to approval of competent counsel selected by, and representing, parties other than the bank.

2. When acting in a fiduciary capacity the bank or trust department except as hereinafter indicated should not appoint as counsel for the estate its own lawyer-officer or other attorney retained to protect the interests of the bank but such counsel as the circumstances of the case and the needs of the estate require; due consideration being given to the preferences of the testator in case of a will, of the donor or creator in case of a voluntary trust, the family of a decedent, an infant or an incompetent person, and of the beneficiaries and other persons interested, in all instances.

3. In the preparation of accounts, upon judicial settlement or otherwise, it is the desire of the trust departments and their officers to adopt such practice as will meet with the approval of the Bar Association, but our experience indicates that trust departments are better equipped for the preparation of the schedules of an account than most law offices. We believe that much time can be saved and greater accuracy obtained if the banks and trust companies are allowed to complete the schedules of accounts under the supervision and subject to the approval of counsel, the remainder of the legal account and the other legal papers, of course, being prepared by counsel.

4. It is well known that the estates of decedents are often subject to taxation in many different jurisdictions. The nature of the tax varies and the methods of procedure

are different in different states. The assessments of an inheritance tax in the State of New York is clearly a legal proceeding and should be conducted by counsel, but many taxes imposed by other jurisdictions upon decedents’ estates seem to involve no more legal procedure than our taxes upon real property. The ascertainment of their amount and the proper payment and discharge of their obligation against an estate is a mere matter of computation and correspondence. We believe that trust departments are competent to deal with such clerical matters, and that, subject to the approval of counsel in each case, the best interests of an estate may often be served by having such work done directly by the trust department. Our motive in suggesting that trust departments perform this service and the preparation of the schedules of an account, without compensation other than the usual commissions, is to expedite the handling of estate. We have a selfish desire to secure a rapid turnover in the business and we believe that not only the parties directly interested but the public at large desire to have the affairs of estates handled with dispatch. Banks and trust companies are organized

with special reference to promptness and accuracy in the dispatch of business. We believe it will be for the best interests of all concerned to make use of such facilities

whenever proper to do so.

5. In conclusion we submit that there are, doubtless, many other questions of propriety and expediency that will arise in the course of the administration of trusts under the intelligent co-operation of attorneys arid banking institutions. We have no doubt that all of them can be answered satisfactorily. We are glad of this opportunity for frank discussion of the subject and hope that it will lead to further conferences, a more complete understanding of details of practice and the establishment of a most cordial relation in the performance of efficient and valuable service to the public."

The two highest codes of ethics ever promulgated govern the trustee and the lawyer. Two great forces, the economic or financial in the trust company, and the learned or professional in the lawyer, need mutual support and confidence in their task of giving general realization to their ideals throughout their respective memberships. With functions so parallel and supplementary of each other we must by mutual concession reach that understanding, confidence and strength that will give the highest standard of fiduciary and professional service the client without whom neither of us can prosper.(Applause.)