When Chief Justice Roberts gave a speech at the Robert H. Jackson Center marking its 10th anniversary, I was one of the three thousand people in attendance. On a field trip for my senior year government class, my days as a Southwestern high school student were coming to a close and I was just excited for an opportunity to be outside the classroom on a beautiful spring day. I had never gone to the Robert H. Jackson Center before, and only knew slightly of the Jamestown native and his connection to the Nuremberg Trials following World War II. However, the Chief Justice’s speech explaining the importance of Justice Robert H. Jackson and of the Center itself left an impact on me, as it did for countless others. Today, over two years after his address, I am here at the Jackson Center working as a summer intern. This extraordinary event celebrated the Center’s 10th anniversary in an unforgettable way, and succeeded in sparking the interest of students, teachers, and locals alike.

When Chief Justice Roberts came to Jamestown, he attended other events in addition to the Jackson Center 10th anniversary ceremony on May 17th. Roberts arrived in Jamestown the day before the ceremony, and attended a dinner reception at the Athenaeum Hotel that evening. There, the Chief Justice was welcomed by roughly two hundred guests with Father Moritz Fuchs, the Honorable William M. Skretny, and Professor David M. Crane serving as guest speakers. Following the dinner, Greg Peterson conducted an interview with Chief Justice Roberts and his former boss during his time at Hogan and Lovells, E. Barrett Prettyman. The talk centered on Roberts’ time working in the private sector, as he could not comment on cases he had dealt with during his time in the Supreme Court. The discussion was a huge success with many interesting stories and laughs shared by all. Very few are aware that a video recording of this interview resides in the Robert H. Jackson Center archives as a result of persistence and persuasion by one of the center’s own, Greg Peterson. Excerpts from the discussion can also be found on the Jackson Center YouTube channel.

The Chief Justice opened his address commenting that fifty-nine years prior the decision of Brown v. Board of Education was announced. The court ruled that the segregation of public school students by race violated the 14th amendment of equal protection under the law, and undid the ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson. Chief Justice Roberts went on to explain how Robert H. Jackson, a member of the Supreme Court at the time, was a part of that decision and “symbolic of his resolve” was present at its announcement even in poor health. Chief Justice Roberts determined that despite Jackson’s death a few months after the decision, “…he left behind an inspiring legacy of a public servant and a true patriot.”

“This center stands as a magnificent monument to this great Justice,” he continued. The Chief Justice praised the Robert H. Jackson Center for its work and its mission over the past years saying, “This center is an appropriate monument to its namesake, who was well known for his learning and eloquence.” He continued to refer to the Jackson Center as a “…dynamic home for study, dialogue and discussion…”

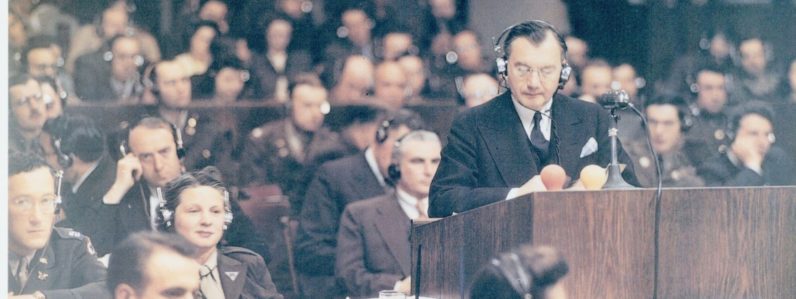

Roberts then gave a brief overview of Robert Jackson’s and career, mentioning his 20 years in Chautauqua County as a “country lawyer.” He remarked how quickly Jackson moved up the ranks after his initial move to Washington at President Franklin Roosevelt’s request. The Chief Justice explained, “In the brief span of eight years he moved from General Counsel of the Bureau of Revenue to Assistant Attorney General in the Justice Department’s Antitrust Division to Solicitor General to Attorney General to Associate Justice of the Supreme Court.” Roberts affirmed that Jackson never used his positions as stepping-stones to further his own career. Instead, as Chief Justice Rehnquist put it, “…he served each of the interests he was bound to serve faithfully and well during the time which he undertook to serve them.” Upon President Truman’s request, he even left his position on the Supreme Court to serve as chief counsel for the United States prosecution of the Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg. Roberts explained that Jackson did this “because the President asked him to serve his country in that capacity.” However, following his return to the court, Jackson had an untimely death at the early age of 62. Despite the short time he had, Jackson left behind a great legacy. Roberts proclaimed, “…What a mark he left…By my count he delivered 154 opinions of the Court.” In the sentences following, the Chief Justice captured the importance of Justice Robert Jackson and the goals of the Jackson Center:

“His decisions reflect extraordinary insight and craftsmanship. Many are and will continue to be loadstars of American jurisprudence. The Jackson Center chronicles that extraordinary career, and it serves as a vibrant reminder that the good works of great men endure beyond their own limited years.”

Chief Justice Roberts went on to explain what he imagined Jackson would think of the Court today. He provided the audience with some of the surprises Justice Jackson would find including a change in schedule for the Justices, renovations, new chambers, altered Court procedure, and a large portrait of himself in the Justices’ conference room, among many other changes.

Chief Justice Roberts then moved to his next and final point, the point the Jackson Center is here to keep alive: Jackson’s view of the proper role of a judge and a lawyer. To do this he recited an old story told by Jackson himself about three stonemasons who were all asked the same question: What were they were doing? The first immediately responded he was “earning a living.” The second said he was “shaping the stone to the pattern.” However, “…the third lifted his eyes skyward and said I am building a cathedral.” Roberts explained each stonemason represents a judge or lawyer. Some view their work as just a way to earn a wage. Others rely solely on precedent when shaping their decisions. “But, some inspired lawyers and judges, like Justice Jackson, have understood that they are participating in a loftier enterprise. The Jackson Center is an enduring monument to that ideal. “ He concluded, “Members of the bench and bar must aim their efforts at working together to build a cathedral: What we call the rule of law.”

After the ceremony concluded, a luncheon was held in the Jackson Center. President of the Center, James C. Johnson led the event and Reverend Maureen Rovegno, the Assistant Director for Religion at the Chautauqua Institution, performed the Invocation. The Honorable Richard J. Arcara, professor John Q. Barrett, and U.S. Congressman Brian Higgins were the main speakers of the Luncheon with Professor David M. Crane performing the closing words.

At 3:00 p.m. the Chief Justice left Jamestown and departed from the Buffalo Airport for Washington D.C.

Tireless planning by countless Center employees and volunteers allowed the Robert H. Jackson Center to celebrate its 10th anniversary in a great way. I, along with around three thousand other students, teachers, and members of the community were able to be part of an event that will not be soon forgotten. This incredible experience allowed the Robert H. Jackson Center to be recognized by a greater audience than ever before, and helped continue the Center’s persistent mission to preserve and advance the legacy of Justice Jackson and his ideas on individual freedom and justice.