Executive Summary

The first forty years after Nuremberg was a period of slow progress in developing international criminal law. There is no doubt that international criminal law has developed in recent years. Indeed if international criminal law is defined as the prosecution of individuals for ‘international crimes’ such as war crimes or Crimes Against Humanity then there was no such law for most of the twentieth century. On the eve of the twentieth century attempts to regulate warfare in The Hague Conference of 1899, and again in 1907, were constrained by notions of State sovereignty. As the Nuremberg judges pointed out in 1946, ‘The Hague Convention nowhere designates such practices [methods of waging war] as criminal, nor is any sentence prescribed, nor any mention made of a court to try and punish offenders.’(1)

The Nuremberg trials established that all of humanity would be guarded by an international legal shield and that even a Head of State would be held criminally responsible and punished for aggression and Crimes Against Humanity. The right of humanitarian intervention to put a stop to Crimes Against Humanity – even by a sovereign against his own citizens – gradually emerged from the Nuremberg principles affirmed by the United Nations.

The awareness of the inadequacy of the law and the willingness to do something to enforce such new principles was slow in coming. The failure of the international community to develop binding norms of international criminal law was glaringly illustrated by the slow pace of various UN committees charged in 1946 with drafting both a code of crimes against the peace and security of mankind and the statutes for an international criminal court.

While the law limped lamely along, international crimes flourished. The horrors of the twentieth century are many. Acts of mass violence have taken place in so many countries and on so many occasions it is hard to comprehend. According to some estimates, nearly 170 million civilians have been subjected to genocide, war crimes and Crimes Against Humanity during the past century. The World Wars lead the world community to pledge that “never again” would anything similar occur. But the shocking acts of the Nazis were not isolated incidents, which we have since consigned to history. Hundreds of thousands and in some cases millions of people have been murdered in, among others, Russia, Cambodia, Vietnam, Sierra Leone, Chile, the Philippines, the Congo, Bangladesh, Uganda, Iraq, Indonesia, East Timor, El Salvador, Burundi, Argentina, Somalia, Chad, Yugoslavia and Rwanda in the second half of the past century.(2) But what is possibly even sadder is that we, meaning the world community, have witnessed these massacres passively and stood idle and inactive. The result is that in almost every case in history, the dictator/president/head of state/military/leader responsible for carrying out these atrocities – despite in Nuremberg – has escaped punishment, justice and even censure.

Not until the world was shocked by the ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia and the genocide in Rwanda could the UN, no longer paralyzed by the Cold War, take action. Nations that had been unwilling to intervene to block the carnage now recognized that some action was essential. For the first time since Nuremberg, a new international criminal tribunal was quickly put in place on an ad hoc basis by the UN Security Council. Under the impetus of shocked public demand, it became possible for the UN Secretariat to draft the statues for the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia in about 8 weeks – the same time it had taken to agree upon the Charter to the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. The ICTY began functioning in 1994. It led to the speedy creation of a similar ad hoc tribunal to deal with genocide and Crimes Against Humanity in Rwanda.

Up until the present the international community has been very reluctant to enforce international criminal law. It has only been done a couple of times in history, without doubt due to the specific circumstances and the political climate at the time. The idea of establishing a permanent international criminal court is not new though. Attempts in that direction were taken as nearly as the end of World War I, but the international community never reached agreement on the matter.

The ICC’s predecessors are primarily the Nuremberg and the Tokyo Tribunals created by the victorious Allies after World War II. These tribunals have been accused of being unfair and merely institutions for “victor’s justice,” but nevertheless they did lay the groundwork for modern international criminal law. They were the first tribunals where violators of international law were held responsible for their crimes. They also recognized individual accountability and rejected historically used defenses based on state sovereignty. These principles of international law recognized in the Nuremberg Charter and Judgments were later affirmed in a resolution by the UN General Assembly.

The International Law Commission (ILC), a body of distinguished legal experts acting at the request of the General Assembly, completed its draft statue for a permanent international criminal court in 1994. In 1996, the ILC finally completed its draft code of crimes against the peace and security of mankind. This new momentum reflected widespread agreement that an international criminal court, with fair trial for the accused, should be created as an essential component of a just world order under law.

After years of work and struggle, the promise of an International Criminal Court with jurisdiction to try genocide, war crimes and Crimes Against Humanity has become a reality. In 1998, the statute of the Court was approved in Rome and it has entered into force the first of July of 2002, when the required number of country ratifications was attained. The Court holds a promise of putting an end to the impunity that reigns today for human rights violators and bringing us a more just and more humane world.

Since the capture of Saddam Hussein in December 2003, there has been intense speculation as to the type of court that will be used to try the former Iraqi president. It now appears that Hussein will be tried by the Iraqi Special Tribunal that was established late in 2003. This Tribunal, which is yet to commence operation, has jurisdiction over the crimes of genocide, war crimes and Crimes Against Humanity committed since 1968. Although it would seem desirable that the former Iraqi dictator be tried by an Iraqi court, it is not yet clear whether the Iraqi Special Tribunal and the Iraqi legal profession have sufficient resources and expertise to conduct a trial of this complexity. Questions also remain as to whether the trial and sentencing of Hussein will conform with international human rights standards and whether it will serve the ends of justice and reconciliation in Iraq.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

International Criminal Law in the Past

Tribunal Milestones

The Agreement of London

The Nuremberg Tribunals

The Influence of Nuremberg

The Case of Saddam Hussein

Conclusion

1. INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL LAW IN THE PAST

International Criminal Law as a concept has exited between nations – states for centuries. Its function is to regulate and prevent criminal international violations, thereby securing and maintaining international legal order and peace. Historically, for activities to be considered international crimes they had to violate domestic regulations. Malekian writes: ”[i}t may be possible to conclude that the basis of international criminal law is the evolution and enforcement of the concept of domestic criminal law. Criminals were extradited to a large extent in order that domestic criminal law be effectively implemented.” This cooperation resulted in, e.g., the conclusion of numerous bilateral and multilateral treaties for the extradition of criminals. (3)

International humanitarian law took its modern form after World War II in order to create a deterrent to the repeat of the horrors that took place in the trenches and concentration camps. Important conventions were agreed on including the European convention on Human Rights (4), the Genocide Convention (5), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (6)and the four Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocols (7) (that protect the civilians and victims of war). By including criminal provisions and obligations for nations these also gave strong notions of a development in international criminal law.

War and law have had a constant relationship between each other ever since the existence of conflict as a collective phenomenon. The regulation of the state of war, whether stemming from tradition, custom, certain codes of conduct and, ultimately, law, has evolved throughout the centuries together with the notion of war.

The idea of a “Crime of War,” or war crime, is not new to the modern legal vocabulary. Unorthodox practices during a war have been branded as war crimes in many scenarios of conflict. However, these war crimes were not in themselves punishable in any international court (mainly due to the practical non-existence of such legal apparatus before the United Nations) and were very much a notion without a consequence, a general concept floating above the aftermath of wars, and not affecting individuals as such but rather relying on the concept of state responsibility. It is only since the development of a doctrine of human rights, of fundamental, documented universal principles, that such crimes have materialized into a legal cast due to the development of the notion of “Crimes Against Humanity” and its derived breaches. The concept of “Crimes Against Humanity” has been a product of very recent historical, political and social developments which has brought war crimes under a different light in international law, and very much under the scope of Human Rights, which have impregnated the law of war as an international, codified phenomenon in many ways. As a provision, it was the initial step that began a whole new approach from part of the international community towards certain abuses against civilians during periods of war and also during peacetime. Certain practices became theoretically “illegal” in a very broad sense within the international community, criminalizing governments, collectives and individuals, whether military or civilian, and covering the commission of crimes both in an individual basis as well as in a collective sense. Conventions have arisen after the appearance of this idea, as well as resolutions and other relevant legislation emanating from international bodies and organisms (mainly the UN). The ultimate reason for these provisions to arise, in theoretical terms and laying aside political considerations, has been the protection of the human being as an individual, regardless of geographical, political or social factors and circumstances, and hence has become a “Human Right,” so to say, in its own right.

Crimes Against Humanity as a new principle saw its birth after the Second World War, as a result of the atrocities committee by the Nazi forces before and during the armed conflict. The establishment of the United Nations in 1945 was in a way the embodiment of the generalized fear for those atrocities ever being committed again, and this institution had a major role in the development of legal doctrines involving concepts such as Crimes Against Humanity, appearing for the first time in a legal and a conceptual form before the Nuremberg Trial in 1945, during the London Agreement of 1945 and its annexed charter setting the grounds for the establishment of a military tribunal.

2. TRIBUNAL MILESTONES

1907

Fourth Hague Convention is held in The Hague, the Netherlands. The convention is the first international agreement outlining the basic rules for land warfare. Among the provisions are prohibitions on mistreating prisoners and protecting the lives and property of civilians.

1945

At the end of World War II, the victorious Allies form the International Military Tribunal to try Nazi German leaders on war crimes charges. Of the 22 men tried by the tribunal, based in Nuremberg, Germany, 19 are convicted.

1946

Allies set up a tribunal in Tokyo to conduct war crimes trials involving 28 Japanese defendants. The defendants face the same charges as those in Nuremberg – Crimes Against Humanity and waging aggressive war.

1948

United Nations General Assembly approves the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide, one of the so-called Geneva Conventions. The agreement specifies that religious or racial genocide is an international crime, and that those who incite genocide or participate in it are to be punished. The following year, diplomats from around the world adopt four new conventions that strengthen the rights during wartime of civilians and prisoners of war. War crimes are defined as offenses that represent “grave breaches” of the convention.

1950

U.N. International Law Commission unveils the seven Nuremberg Principles. The basic premise of the principles is that no accused war criminal in any place or time is above the law.

1992

Bosnia-Herzegovina, one of the remaining Yugoslav republics, declares independence. A three-sided civil war breaks out among Bosnia’s Moslems, Croats and Serbs. Serbs initiate a policy of “ethnic cleansing,” or forcibly removing people from their homes in an effort to create ethnically pure regions, and detain many non-Serbs in concentration camps.

1993

The U.N. Security Council agrees to establish the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), to be based in The Hague, to try war crimes cases.

1994

Inter-ethnic strife explodes in Rwanda. More than 500,000 people, most of them members of the Tutsi minority, are massacred by the Hutu majority over a four-month period. In November, the Security Council agrees to establish the International Criminal Tribunal in Rwanda (ICTR) in Arusha, Tanzania.

1995

A cease-fire is negotiated in Bosnia in October, and combatants sign a peace treaty, in Dayton, Ohio. Troops from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) begin patrolling in Bosnia in December.

1996

The ICTY imposes its first sentence on Drazen Edemovic, a Bosnian Croat who served in the Bosnia Serb army. Edemovic pleads guilty, so he is sentenced without a trial to ten years in prison.

1997

In May, the first full-length ICTY trial concludes with the conviction of Bosnian Serb Dusan Tadic on eleven charges of war crimes.

1998

After fifty years of discussion and documentation on the need for an international criminal court, the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court was adopted on July 17, 1998.

1998

Augusto Pinochet, the former Chilean dictator, was arrested by British authorities. He was extradited on charges of genocide, torture, and other crimes during his rule in the 1970s – 80s.

1999

Slobodan Milosevic, Milan Milutinovic, Vlajikovic, and Nikola Sainovic were indicted by The Hague.

2002

The ICC entered into force on July 1, 2002, establishing “an independent permanent International Criminal Court in relationship with the United Nations system, with jurisdiction over the most serious crimes of concern to the international community as a whole.”

2003

U.S.-led military coalition ousts Saddam Hussein from power. He is captured on December 13, 2003.

3. THE AGREEMENT OF LONDON

Robert H. Jackson made a preliminary visit to London in late May 1945 where he conferred with Foreign Minister, Anthony Eden, and British Attorney General, David Maxwell Fyfe. These meetings ultimately helped to show that there was no significant difference between the American and British goals for the trials. However, before meeting with the British the American delegation felt that they would have a difficult time in convincing opponents that the American plan for holding a trial, rather than executing the war criminals, would be the best option. They expected to have the greatest difficulty with the British because they would naturally want to assume the leadership role in the trial.

On Monday, June 18, 1945, Jackson and seventeen members of his staff, including Major General William J. Donovan, the director of the O.S.S., and Ensign William E. Jackson, Justice Jackson’s son, departed to begin negotiations for a charter with the British, French, and Russians in London. On June 21 representatives from the United States and Britain met on an informal basis to exchange information. The representative from the British Foreign Office, Sir Basil Newton, informed the American delegation that the government had accepted the invitation to the conference and would arrive on June 25. The British and Americans agreed that the trial should be held on the Continent, probably in Munich but Justice Jackson pointed out that the location would depend on availability of the facilities. At a second meeting on June 24 Sir Basil Newton informed both delegations that the Russians had accepted the invitation but had asked for the first official meeting to be delayed until June 26. Throughout the negotiations the Americans and the Russians would almost continually be at odds with each other.

The British delegation consisted of Sir David Maxwell Fyfe, Sir Thomas Barnes, the Treasurer-Solicitor and Patrick Dean, of the British Foreign Office. The French delegation consisted of Judge Robert Falco and Professor André Gros. General I.T. Nikitchenko and Professor Trainin made up the Russian delegation.

The Anglo-American system of law differed considerably from the continental system that the French and the Russians used. The first point of contention was over the function of the indictment. In Anglo-American law this is the statement of charges against a criminal to inform him of the crime he is being charged with. In the Soviet system the indictment includes all of the evidence that will be utilized during the trial. In this case, the Americans won. A second point of disagreement between the Americans and the Russians was whether organizations, such as the SS and the Gestapo, could be tried as criminal entities. The Russians said no and the Americans said yes. Giving the Americans the responsibility for proving this portion of the case solved this problem. Conflicts also arose in regard to the definition of international law and what constituted both international law and the laws of a sovereign nation. The negotiating countries faced many disagreements of this nature. Adjourning the conference, preparing new amendments and then debating these amendments at the next session helped to solve each problem but on many major points of contention the American delegation overrode opposition from the other nations.

Throughout the negotiations Justice Jackson attempted to keep an open mind, which probably eased tensions, but the Agreement of London basically created a system that the Americans approved of and the other nations went along with. The negotiators ran into many points of disagreement but in the end, Justice Jackson and his British, French and Russian counterparts were able to overcome differences in judicial practice to form the tribunal.

On August 8, 1945, the participating nations gathered to sign the Agreement and Charter for the Prosecution and Punishment of Major War Criminals of the European Axis, or the Agreement of London. The process of creating this charter had taken two months of negotiation but succeeded in establishing a system that all four nations would accept as the dispensing justice.

The final London Agreement created the system on which the surviving Nazi leaders and Nazi criminal organizations would be tried. The statute drew up four counts of crimes for which the German leadership would be tried. The first count involved conspiracy – conspiring to engage in the other three counts. Count two was “crimes against peace” – the actual planning, preparing, and waging of aggressive war. That count was generally interpreted as criminalizing the waging of war to alter the status quo. Thus, the Germans could not use the unfairness of the Versailles Treaty to justify making war to bring about is revision.

The third count was “war crimes” – a category that included killing and mistreating soldiers and civilians in ways not justified by military necessity. Count four consisted of “Crimes Against Humanity,” which was a new idea, dealing with inhuman actions committed against civilians. Included in count four was the mass murder of Jews.

The London Statute called for the indictment of the major war criminals, and after much debate, the IMT came up with a list of 24 names, 22 of whom would, in the event, be tried. Among those listed were Herman Goering, Joachim von Ribbenstrop, Admiral Karl Donitz, General Alfred Jodl, Alfred Rosenberg, Albert Speer, Ernst Kaltenbrunner, Hans Frank, and Julius Streicher. Martin Bormann, who is now believed to have died prior to the indictment, would be tried in absentia. Also indicted were the leading organizations of the third Reich – the Reich Cabinet, the Nazi Party leadership, the SS, the Gestapo, the General Staff, and the SA.

Upon signing the London Agreement creating the basis for and existence of the International Military Tribunal, Jackson stated: “For the first time, four of the most powerful nations [U.S., France, Great Britain, Soviet Union] have agreed not only upon the principle of liability for war crimes of persecution, but also upon the principle of individual responsibility for the crime of attacking international peace.” (8)

3.1 Copy of the Agreement

London Agreement of August 8, 1945

Agreement of the government of the United States of America, the Provisional Government of the French Republic, the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics for the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the European Axis

WHEREAS the United Nations have from time to time made declarations of their intention that War Criminals shall be brought to justice;

AND WHEREAS the Moscow Declaration of the 30th October 1943 on German atrocities in Occupied Europe stated that those German officers and men and members of the Nazi Party who have been responsible for or have taken a consenting part in atrocities and crimes will be sent back to the countries in which their abominable deeds were done in order that they may be judged and punished according to the laws of these liberated countries and of the free governments that will be created therein;

AND WHEREAS this Declaration was stated to be without prejudice to the case of major criminals whose offenses have no particular geographical location and who will be punished by the joint decision of the Governments of the Allies;

NOW THEREFORE the Government of the United States of America, the Provisional Government of the French Republic, the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (hereinafter called “the Signatories”) acting in the interests of all the United Nations and by their representatives duly authorized thereto have included this Agreement.

Article 1.

There shall be established after consultation with the Control Council for Germany an International Military Tribunal for the trial of war criminals whose offenses have no particular geographical location whether they be accused individually or in their capacity as members of the organizations or groups or in both capacities.

Article 2.

The constitution, jurisdiction and functions of the International Military Tribunal shall be those set in the Charter annexed to this Agreement, which Charter shall form an integral part of this Agreement.

Article 3.

Each of the signatories shall take the necessary steps to make available for the investigation of the charges and trial the major war criminals detained by them who are to be tried by the International Military Tribunal. The signatories shall also use their best endeavors to make available for investigation of the charges against and the trial before the International Military Tribunal such of the major war criminals as are not in the territories of any of the signatories.

Article 4.

Nothing in this Agreement shall prejudice the provisions established by the Moscow Declaration concerning the return of war criminals to the countries where they committed their crimes.

Article 5.

Any government of the United Nations may adhere to this agreement by notice given through the diplomatic channel to the Government of the United Kingdom, who shall inform the other signatory and adhering governments of each such adherence.

Article 6.

Nothing in this Agreement shall prejudice the jurisdiction or the powers of any national or occupation court established or to be established in any allied territory or in Germany for the trial of war criminals.

Article 7.

This Agreement shall come into force on the day of signature and shall remain in force for the period of one year and shall continue thereafter, subject to the right of any signatory to give, through the diplomatic channel, one month’s notice of intentions to terminate it. Such termination shall not prejudice any proceedings already taken or any findings already made in pursuance of this Agreement.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF the Undersigned have signed the present Agreement.

DONE in quadruplicate in London this 8th day of August 1945 each in English, French, and Russian, and each text to have equal authenticity.

For the Government of the United States of America

[signed] ROBERT H. JACKSON

For the Provisional Government of the French Republic

[signed] ROBERT FALCO

For The Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

{signed] JOWITT C.

For the Government of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

[signed] I.T. NIKITCHENKO

[signed] A.N. TRAININ

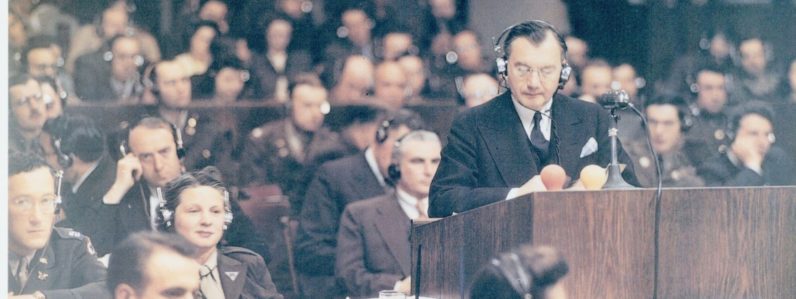

4. THE NUREMBERG TRIBUNALS

4.1 the International Military Tribunal (IMT)

Three months after the end of World War II the United States, Great Britain, the Soviet Union and France, signed an agreement creating the International Military Tribunal (IMT), known as the “Nuremberg Tribunal,” for the Prosecution and Punishment of the Major War Criminals of the European Axis. Only four categories of crimes were to be punished:

Conspiracy (conspiring to engage in the other three counts),

Crimes Against Peace (planning, preparing and waging aggressive war),

War Crimes (condemned in Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907) and

Crimes Against Humanity (such as genocide), which by their magnitude, shock the conscience of humankind.

Each provision of the 30-articles was carefully considered in order to reach an accord that seemed fair and acceptable to the four partners representing the United States, Great Britain, France and the Soviet Union. On the eight day of August 1945, the Charter was signed and the first International Military Tribunal in the history of mankind was thereby inaugurated.

A Chief Prosecutor had been appointed for each of the four victorious powers. Designated by President Harry S. Truman as U.S. representative and chief counsel at the IMT Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson planned and organized the trial procedure and served as Chief Prosecutor for the USA. He set the tone and goals: “That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to Reason…We must never forget that the record on which we judge these defendants today is the record on which history will judge us tomorrow. To pass these defendants a poisoned chalice is to put it to our own lips as well. We must summon such detachment and intellectual integrity to our task that this trial will commend itself to posterity as fulfilling humanity’s aspirations to do justice.” (9)

From November 20, 1945, until August 31, 1946, all sessions of the tribunal were held in Nuremberg under the presidency of Lord Justice Geoffrey Lawrence. In its comprehensive judgment, the Tribunal traced the history of international criminal law and the growing recognition in treaties, conventions and declarations, that aggressive war was an illegal act for which even a head of state could be brought to account. There was no longer anything ex facto about such a charge. Leaders who deliberately attacked neighboring states without cause must have know that their deeds were prohibited and it would be unjust to allow them to escape merely because no one had been charged with that offense in the past. “The law is not static” said the Tribunal, “but by continued adaptation follows the needs of a changing world.” Aggressive war was condemned as “the supreme international crime.” (10)

The evidence, based in large part on captured German records, was overwhelming that crimes of the greatest cruelty and horror had been systematically committed pursuant to official policy. The IMT, citing The Hague Conventions and prevailing customs of civilized nations, rejected Germany’s argument that rules of war had become obsolete and that “total war” was legally permissible. Regarding Crimes Against Humanity (such as extermination and enslavement of civilian populations on political, racial or religious grounds), the law took another step forward on behalf of humankind - a step that was long overdue. The findings and judgment of the IMT helped to usher in a new era for the legal protection of fundamental human rights.

The lead IMT defendant, Field Marshal Hermann Goering, after he was sentenced to be hanged, was sentenced to death in absentia. Other defendants were hanged or sentenced to long prison terms. Some were acquitted and released. The Charter was adhered to by nineteen other nations and both Charter and Judgment of the IMT were unanimously affirmed by the first General Assembly of the United Nations. They have become expressions of binding common international law.

4.2 Principles of the Nuremberg Tribunal, 1950 NO. 82

The Definition of what constitutes a war crime is described by the Nuremberg Principles, a document that came out of this trial.

Principles of International Law Recognized in the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal and in the Judgment of the Tribunal. Adopted by the International Law Commission of the United Nations, 1950. (11)

Under General assembly Resolution 177 (II), paragraph (a), the International Law Commission was directed to “formulate the principles of international law recognized in the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal and in the judgment of the Tribunal.” Since the Nuremberg Principles had been affirmed by the General Assembly, the task entrusted to the Commission was not to express any appreciation of these principles as principles of international law but merely to formulate them. The text below was adopted by the Commission at its second session. The report of the commission also contains commentaries on the principles. (12)

Principle I

Any person who commits an act which constitutes a crime under international law is responsible therefore and liable to punishment.

Principle II

The fact that internal law does not impose a penalty for an act which constitutes a crime under international law does not relieve the person who committed the act from responsibility under international law.

Principles III

The fact that a person who committed an act which constitutes a crime under international law acted as Head of State or responsible Government official does not relieve him from responsibility under international law.

Principle IV

The fact that a person acted pursuant to order of his government or of a superior does not relieve him from responsibility under international law, provided a moral choice was in fact possible to him.

Principle V

Any person charged with a crime under international law has the right to a fair trial on the facts and law.

Principle VI

The crimes hereinafter set out are punishable as crimes under international law:

1. Crimes Against Peace:

a. Planning, preparation, initiation or waging of a war of aggression or a war in violation of international treaties, agreements or assurances;

2. War Crimes:

Violations of the laws or customs of war which include, but are not limited to, murder, ill-treatment or deportation to slave-labor or for any other purpose of civilian population of or in occupied territory, murder or ill-treatment of prisoners of war, of persons on the seas, killing of hostages, plunder of public or private property, wanton destruction of cities, towns, or villages, or devastation not justified by military necessity.

3. Crimes Against Humanity:

Murder, extermination, enslavement, deportation and other inhuman acts done against any civilian population, or persecutions on political, racial or religious grounds, when such acts are done or such persecutions are carried on in execution of or in connection with any crime against peace or any war crime.

Principle VII

Complicity in the commission of a crime against peace, a war crime, or a crime against humanity as set forth in Principles VI is a crime under international law.

4.3 Twelve Subsequent Trials at Nuremberg

Contrary to the original plans, no subsequent international tribunal took place because the four Allies were unable to agree on joint subsequent trials.

As a compromise, the quadripartite Control Council that governed Germany enacted a law authorizing each of the four Powers to carry on with such prosecution in its own zone of occupation as it might see fit. From 1947-1949, twelve U.S. military trials involving politicians, military personnel, businessmen and industrialists, doctors, lawyers, members of the Foreign Office, etc., were held in Nuremberg. Similar trials were conducted in the French, British and Soviet zones of occupation.

5. THE INFLUENCE OF NUREMBERG

5.1 Influence on the Development of International Criminal Law

5.1.1 The United Nations

The Nuremberg Principles and the conception of Crimes Against Humanity did not only affect the formation of International War Crimes Tribunals. Its impact caused several effects beyond creating a mere term to be used in military tribunals and political purposes. One of these effects was the United Nations Resolution 96 (1), drawn up on the 11th of December 1946, stating that “…genocide is a crime under international law, contrary to the spirit and aims of the United Nations and condemned by the civilized world.” Deriving from the Nuremberg concept of Crimes Against Humanity, and the crimes perpetrated by the Nazis in their total war, this declaration was finally embodied two years later in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of 1948. This convention criminalized genocide and related activities in the international sphere, and the convention itself is heavily influenced by many of the Nuremberg principles. It also extended this crime against humanity beyond periods of war and the specific scenario of the Second World War. The Genocide Convention was not, per se, a major advancement in the upholding of international human rights, especially considering its provision in Articles V and VI, which provide that states should regulate their legal systems accordingly to criminalize such acts in the domestic sphere, and that those found guilty of the crime of genocide should be tried in the courts of the country where the acts were committed in absence of a competent international tribunal with consented jurisdiction over the matter, and many academics have shown to be quite skeptical about its practical possibilities. However, on the theoretical arena the Convention Against Genocide is a development from the precepts set in Nuremberg, in such a sudden and ad hoc manner, especially where codification of Crimes Against Humanity is concerned. The Convention takes the main aspect of these crimes, extirpates it from a broad definition, and narrows it down into one separate and codified principle. Genocide as defined in Articles II and III practically cover all those measures taken by the Nazis during their persecution and brutal extermination of certain social, religious and cultural groups: those same atrocities which the members of the Court dubbed as Crimes Against Humanity took concrete form in this Convention.

In 1948 the United Nations issued the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the first legal document to recognize such rights as binding, and creating the notion of Human Rights as we understand it today. The influence which Nuremberg and to a certain extent the Tokyo trials had upon the formulation and conception of such a declaration cannot be understated. Nuremberg had for the first time in international law traced a definite distinction between jus ad bello a doctrine concerned exclusively on the conduct in warfare, and jus ad bellum, which concerns itself with the justice or legality of the waging of war. By introducing the new principles of Crimes Against Peace and Crimes Against Humanity, Nuremberg effectively fathered a globalized concern towards certain attitudes in war and, by extension, for the rights of all human beings suffering the effects of certain modes of violence. This supposed impact on the Universal Declaration has been backed up by the fact that some academics have stated that the UN Charter itself was almost a product of Nuremberg and the issues raised before, during and after the Trial.

5.1.1.1 Codification of Law via the United Nations

The first General Assembly of the new U.N. unanimously affirmed the legal principles laid down in the Charter and Judgment of the IMT: aggression, war crimes and Crimes Against Humanity were punishable crimes for which even a head of state could be held to account. Superior orders would be no excuse but could be considered in mitigation. Inspired by the horrors revealed at the Nuremberg Trials, the Assembly passed another resolution calling for a convention to prohibit and punish the crime of genocide – by such a tribunal as might later prove acceptable to the parties. Experts were soon designated to draw up a Code of Crimes Against the Peace and Security of Mankind and to draft statutes for an international criminal court to punish such offenses.

5.1.2 The Geneva Conventions

The U.N., which was founded in 1945 from the ashes of World War II, took the lead in the late 1940s in defining war crimes and trying to establish guidelines designed to prevent such horrors in the future. In December 1948, the U.N. General Assembly passes a resolution called the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide. The resolution was one of the so-called Geneva conventions, named after the Swiss city where they were signed.

In the 1948 convention, genocide was defined as certain acts “committed with the intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such.” Article I of the convention stated, “The contracting parties confirm that genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law which they undertake to prevent and to punish.” Article 3 read in part, “The following acts shall be punishable: genocide; conspiracy to commit genocide; direct and public incitement to commit genocide; attempt to commit genocide; complicity in genocide.” The list of punishable crimes was derived directly from the Nuremberg prosecutors’ charges.

The Fourth Geneva Convention, agreed to by the General Assembly in 1949, also dealt with war crimes. Known formally as the Convention on the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, it required U.N. nations to enact laws that made it illegal to commit or order others to commit “grave breaches” of the Convention, and to actively seek to bring such offenders to trial. The grave breaches, which constitute the heart of the contemporary definition and understanding of war crimes, include various acts committed against protected persons and property, including “willful killing, torture or inhumane treatment…willfully causing great suffering or serious injury to body or health, unlawful deportation or transfer or unlawful confinement of a protected person.”

5.2 War Crimes Trials After Nuremberg

The International Military Tribunal in particular, and the twelve subsequent trials at Nuremberg, laid the basic foundations for the later development of international criminal law.

5.2.1 Tokyo

During the same year as Nuremberg, the Tokyo Trials were set up by the United States in order to prosecute and bring to justice several Japanese officials involved in war crimes and Crimes Against Humanity. During the Tokyo trials extensive reference was made to Nuremberg and its definition of Crimes Against Humanity. Accordingly to several academics, Article 6 C of the Charter drafted in the London Agreement was in a way formulated exclusively with the thought of prosecuting the Nazi leaders held responsible for the atrocities committed against the Jewish people and other targeted groups both inside and outside Germany. The Tokyo trials were not only a proof that the Nuremberg Principles allowed a margin of operation for other cases, but also presented the initiation of a series of tribunals which would uphold, under the specific circumstances stated by the treaty (ie, “…. committed against any civilian population, before or during the war, or prosecutions on political, racial or religious grounds in execution of or in connection with any crime within the jurisdiction of the Tribunal.”), the same possibility of prosecution for Crimes Against Humanity. Tokyo was the first stepping-stone from Nuremberg, which would lead to the universalization of Crimes Against Humanity and its relevant derivations.

5.2.2 Yugoslavia

In the early 1990s, the Cold War had ended, and most formerly Communist nations were beginning the difficult transition to democracy and capitalism. The end of tight Communist control in Eastern Europe also unleashed long-suppressed nationalism among ethnic groups.

In 1991, two of Yugoslavia’s four republics, Slovenia and Croatia, declared independence. Ethnic-based conflict broke out almost immediately, prompted largely by the resistance to independence of large Serb minorities in Croatia.

In 1992, the Security Council established a Commission of Experts to investigate evidence of violations of humanitarian law in the territory of the former Yugoslavia.

The accounts of atrocities in the early years of the Bosnian Civil War prompted the creation of the first international war-crimes court since Nuremberg and Tokyo. In May 1993, the U.N. Security Council formally established the ICTY (Res. 827). The new court, with its seat in The Hague was given responsibility for prosecuting crimes that violated the Geneva Conventions, including genocide and Crimes Against Humanity. For the first time ever, rape was recognized as a crime against humanity when it was included in the ICTY’s mandate.

The ICTY’s first indictment was handed down in November 1994. As of September 1997, a total of 78 individuals have been publicly indicted by the Court. Fifty-seven of those indicted are Serbs, 18 are Croats and 3 are Moslems. The court handed down its first sentence in November 1996, sentencing Drazen Edemovic, a Croat who served in the Bosnian Serb Army, to ten years in prison for his role in the Srebrenica massacre.

5.2.3 Rwanda

In 1994, brutal civil war erupted between rival ethnic tribes in Rwanda. There were reports that perhaps half a million Tutsi and their supporters were being savagely massacred by the dominant Hutu government. The Security Council sent a small commission to investigate (Res. 935, July 1994) and it soon reported back that the crimes being committed were horrendous. United Nations forces were dispatched to Rwanda to help restore order to that battered country.

The Statute for the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda was adopted at the end of 1994 (Res. 955). It followed closely the general outlines of the ICTFY but was more explicit in assuring that even in a civil conflict violations of the rules of war would not be tolerated. The Court was authorized to prosecute for genocide, Crimes Against Humanity and war crimes regardless of whether the strife was called an international conflict or a civil war. Because of the nature of the internal conflict, the inclusion of aggression as a crime within the jurisdiction of the court was not relevant. Only the specified crimes committed within the defined area during the year 1994 could be dealt with. The Rwanda Court was thus a special tribunal of very limited jurisdiction.

5.3 The International Criminal Court (ICC)

After years of work and struggle, the promise of an International Criminal Court with jurisdiction to try genocide, war Crimes Against Humanity has become a reality. In 1998, the statute of the Court was approved in Rome and it has entered into force the first of July 2002, when the required number of country ratifications was attained. The court holds a promise of putting an end to the impunity that reigns today for human rights violators and bringing us a more just and more humane world.

5.3.1 Historical Introduction

The Nuremberg and Tokyo trials were founded on the wish that atrocities similar to those that had taken place during the Second World War would “never again” recur. In 1948 the U.N. General Assembly adopted a resolution reciting that “[i]n the course of development of the international community, there will be a an increasing need of an international judicial organ for the trial of certain crimes under international law.” (13) Initiatives to create such an institution were taken as early as 1937 by the League of Nations that formulated a convention for the establishment of an international criminal court, but the Cold War led to deadlock in the international community and the matter fell into oblivion. Sadly we realize that the cruelties during World War II were not isolated incidents. Genocide has since Nuremberg taken place in Uganda, in Cambodia, in Rwanda, in Somalia, in Bosnia, and the list could go on.

Not until the world was shocked by the ethnic cleansing in the former Yugoslavia and the genocide in Rwanda could the UN, no longer paralyzed by the Cold War, take action. In response the Security Council, basing its decisions on Chapter VII of the UN Charter, commissioned two ad hoc international criminal tribunals (the ICTY for the former Yugoslavia and the ICTR for Rwanda) to investigate alleged violations and to bring the perpetrators to justice. Without doubt, these courts have significantly contributed to the development of international criminal law, but they have not been entirely successful. Their biggest problems have been the lack of formal means of enforcement to seize indicted criminals. After the Cold War tensions had dissolved the world community showed a renewed interest in creating an international criminal court. On December 4, 1989, the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution that instructed the International Law Commission (the ILC) to study the feasibility of the creation of a permanent ICC. Four years later, and obviously pleased with the ILC’s report, the General Assembly called on the Commission to commence the process of drafting a statute for the court. This statute was presented in 1994. The following year a preparatory committee was established to further review the substantive issues regarding the creation of a court based on the ILC report and statute. The aim was to prepare a convention for the ICC that had the prospects of being widely accepted globally.

The International Criminal Court (ICC) was established by the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court on 17 July 1998, when 120 states participating in the “United Nations Diplomatic Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Establishment of an International Court” adopted the statute. This is the first ever permanent, treaty-based, international criminal court established to promote the rule of law and ensure that the gravest international crimes do not go unpunished.

The statute sets out the Court’s jurisdiction, structure and functions and it provides for its entry into force 60 days after 60 states have ratified or acceded to it. The 60th instrument of ratification was deposited with the Secretary General on 11 April 2002, with ten countries simultaneously deposited their instruments of ratification. Accordingly, the statute entered into force 1 July 2002. Anyone who commits any of the crimes under the statute after this date will be liable for prosecution by the Court. (14)

6. THE CASE OF SADDAM HUSSEIN

6.1 A Brief Background to the Iraqi Crises

When Iraq in August 1990, led by its dictator Saddam Hussein, committed brazen aggression by attacking its friendly neighboring Arab state of Kuwait, the sleeping giant of international law began to stir. The Security Council of the Untied Nations responded promptly with a barrage of resolutions followed by action under Article VII of the UN Charter authorizing the use of military force to expel Iraq and restore peace. An allied coalition led by the United States immediately began to bombard Iraqi troops.

After Iraq was routed, the Council imposed a host of new conditions and sanctions designed to secure peace in the area in the future. What was glaringly absent was U.N.-authorized action to bring to justice those who were responsible for the aggression, the Crimes Against Humanity and the clear violations of the laws of war that accompanied Iraq’s unlawful invasions of Kuwait.

Instead of following the Nuremberg principle of punishing only the guilty after a fair trial, economic sanctions were imposed on the civilian population of Iraq – many of whom might have disagreed with the aggressive policies of their government. Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s former despotic leader, remained at the head of the government and thumbed his nose at the world community’s efforts to curb his production of weapons of mass destruction. The lessons of Nuremberg seemed to have been forgotten. (15)

6.2 What Crimes are Saddam Hussein Accused Of?

They cover acts between July 17, 1968, when Hussein and other Ba’ath Party members took power in a coup, and May 1, 2003, when President Bush declared the end of major combat operations. Those years saw hundreds of deaths, the use of chemical weapons against Iranians and Kurds, the invasion of Kuwait in 1991, the massacre of Sh’ites and Marsh Arabs who rose up after the first Gulf War, and alleged systematic killings, rapes and tortures.

6.3 What Kind of Trial?

Since the capture of Saddam Hussein in December 2003, there has been intense speculation as to the type of court that will be used to try the former Iraqi president. It now appears that Hussein will be tried by the Iraqi Special Tribunal that was established in 2003. This Tribunal, which is yet to commence operation, has jurisdiction over crimes of genocide, war crimes and Crimes Against Humanity committed since 1968. Although it would seem desirable that the former Iraqi dictator be tried by an Iraqi court, it is not yet clear whether the Iraqi Special Tribunal and the Iraqi legal profession have sufficient resources and expertise to conduct a trial of this complexity. Questions also remain as to whether the trial and sentencing of Hussein will conform with international human rights standards and whether it will served the ends of justice and reconciliation in Iraq.

Having the Iraqis themselves try Saddam avoids the imperialism perception a U.S.-led trial would perpetuate. The victors won’t be trying the vanquished, the people Hussein terrorized will. Iraqi council members have assured their citizens they will televise the trial, so that everyone can see Saddam getting his day in court and understand the depth and breadth of the atrocities he and his regime committed. Many experts believe the Iraqi people need this public airing of Hussein’s sins, in order to “move on” and really begin living in a post-Saddam world. A state department official was quoted in Time magazine saying, “There’s an Iraqi catharsis that needs to take place.”

While the Iraqis trying Iraqis option has a lot of merit, it had drawbacks that President Bush, England’s Prime Minister Tony Blair and others may be missing. First, the focus would be on Saddam’s crimes against his own people. While they are worthy accusers, they are not the only people against whom Hussein committed crimes. Iran wants Saddam tried for starting the Iran-Iraq War in 1980. Kuwait wants him tried for invading that country in 1991. Israel wants to know whether scud missile attacks are war crimes.

The other – and ultimately more important – drawback is that by not trying him in front of an international body, such as the U.N.’s International Criminal Tribunal, the charter of the United Nations itself and of the concept of the world collectively bringing despots to justice are gutted. The noble precedents set by the Nuremberg trials of the Nazis after World War II and the recent trials addressing the war crimes in the Yugoslavia and Rwanda would be ignored.

Some may say “good riddance,” since the U.N. hasn’t been very effective lately. But, marginalizing the U.N. by not having it try Saddam on behalf of the rest of the world further increases the chances that the USA will be stuck with full tab for Saddam’s ouster and the rebuilding of Iraq. A better strategy would be to attempt to use Saddam’s capture and subsequent trial as a “bridge” to accelerate Iraq’s reentry into the world’s community of nations – and vice versa.

7. Conclusion

International crimes, particularly war crimes and Crimes Against Humanity, have been, regrettably, all too common. Ongoing violence and widespread civil unrest continue in numerous situations, those responsible for atrocities have rarely faced justice. With a substantially increased risk of further terrorist attacks in the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attacks and the Bali bombings, the development of appropriate legislative and institutional responses to international crimes has acquired a new urgency.

For more than four decades after the establishment of the Nuremberg and Tokyo tribunals the enforcement of international criminal law remained an exclusively national responsibility and the report card is appalling. The abject failure of an exclusive reliance on national courts and legal processes to rein in impunity for the perpetration of atrocities is the single most compelling argument for an effective international criminal law regime. This is not to suggest that the international community needs an effective international regime to replace or supplant national courts and processes. Rather, the suggestion here is for an effective international supplement to national structures and processes – a multilateral institutional framework to hold some key individuals to account while simultaneously providing a catalyst for more effective national enforcement of international criminal law.

The Nuremberg Tribunals were a precedent and a promise. As part of the universal determination to avoid the scourge of war, legal precedents were created that outlawed wars of aggression, war crimes and Crimes Against Humanity. The implied promise held forth to the world was that such crimes would be condemned in future, wherever they occurred and that no person or nation would be above the law. After half a century, it now seems possible that the promise may yet to be fulfilled.

International criminal law is undergoing a rapid transformation. One of the most important events in this evolution was the coming into force of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (the “ICC”) on July 1, 2002. There is no doubt that the international community is entering a new era in which perpetrators of international crimes will no longer enjoy impunity.

The creation of the new international Criminal Court will prove a catalyst for states to take the national enforcement of international human rights law much more seriously than has hitherto been the case. Many states, recognizing the potential scope of the International Criminal Court’s jurisdiction – particularly in relation to the so-called “principle of complementarity” – have already enacted broad-ranging criminal legislation to ensure that all the crimes within the Rome Statute are covered by domestic penal law. The overwhelming motivation for this unprecedented criminal law reform is to maximize the potential benefits of the principle of complementarity in the event of allegations against a State’s own nationals.

The Rome Statute is one of the sources of international criminal law. The pre-existing sources on which the Statute was built not only include rules of international humanitarian law, and in particular those contained in the Geneva Conventions and their additional protocols, but also the rules and categories established under the Nuremberg and Tokyo War Tribunals – “war crimes,” “Crimes Against Humanity,” and the crime of “aggression.” Another important source includes the experience gained from the ad hoc tribunals created by the UN Security Council – the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda.

Endnotes:

1 Cited by Andres Clapham in From Nuremberg to The Hague: The Future of International Criminal Justice, Philippe Sands, Cambridge University Press, 2003, p. 31

2 White, Jamison G., Nowhere to run, Nowhere to hide: Augusto Pinochet, Universal Jurisdiction, the ICC,and a Wake-up Call for the Former Heads of State, 1999 and Scharf, Michael P., Results of the Rome Conference for an International Court, 1998.

3 Malekian, Farhad, International Criminal Law – The Legal and Critical Analysis of International Crimes,” 1991, p. 1,2, and 9.

4 The European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedom (1950).

5 The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948) (The Genocide Convention)

6 The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948); GA Resolution 217A (III)

7 The four Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Additional Protocol I and II of 1977. The Geneva Convention as drafted in 1949 evolved from 19th century protocols (1864).

8 Jackson, Robert H. Statement of Chief Counsel Upon Signing of the Agreement, 19 Temp, I.Q 169 [1945-6]

9 cite R.H. Jackson, The Case Against the Nazi War Criminals (NY, Knopf, 1946, pp 3-7)

10 For cite see ICC, p. 72-73.

11 Authentic text: English Text published in Report of the International Law Commission Covering its Second Session, 5 June – 29 July 1950, Document A/1316, pp. 11-14.

12 Yearbook of the International Law Commission, 1950, Vol. II, pp 374-378.

13 United Nations Doc. A/760, Dec. 5, 1948.

14 King and Theofrastous, From Nuremberg to Rome: A Step Backward for U.S. Foreign Policy and Barrett, Mathew A., Ratify or Reject: Examining the United States’ Opposition to the International Criminal Court, 1999.

15 Benjamin B. Frencz, The Legacy of Nuremberg International Criminal Courts – Blaine Sloan Lecture, published in The Pace International Law Review 1997.