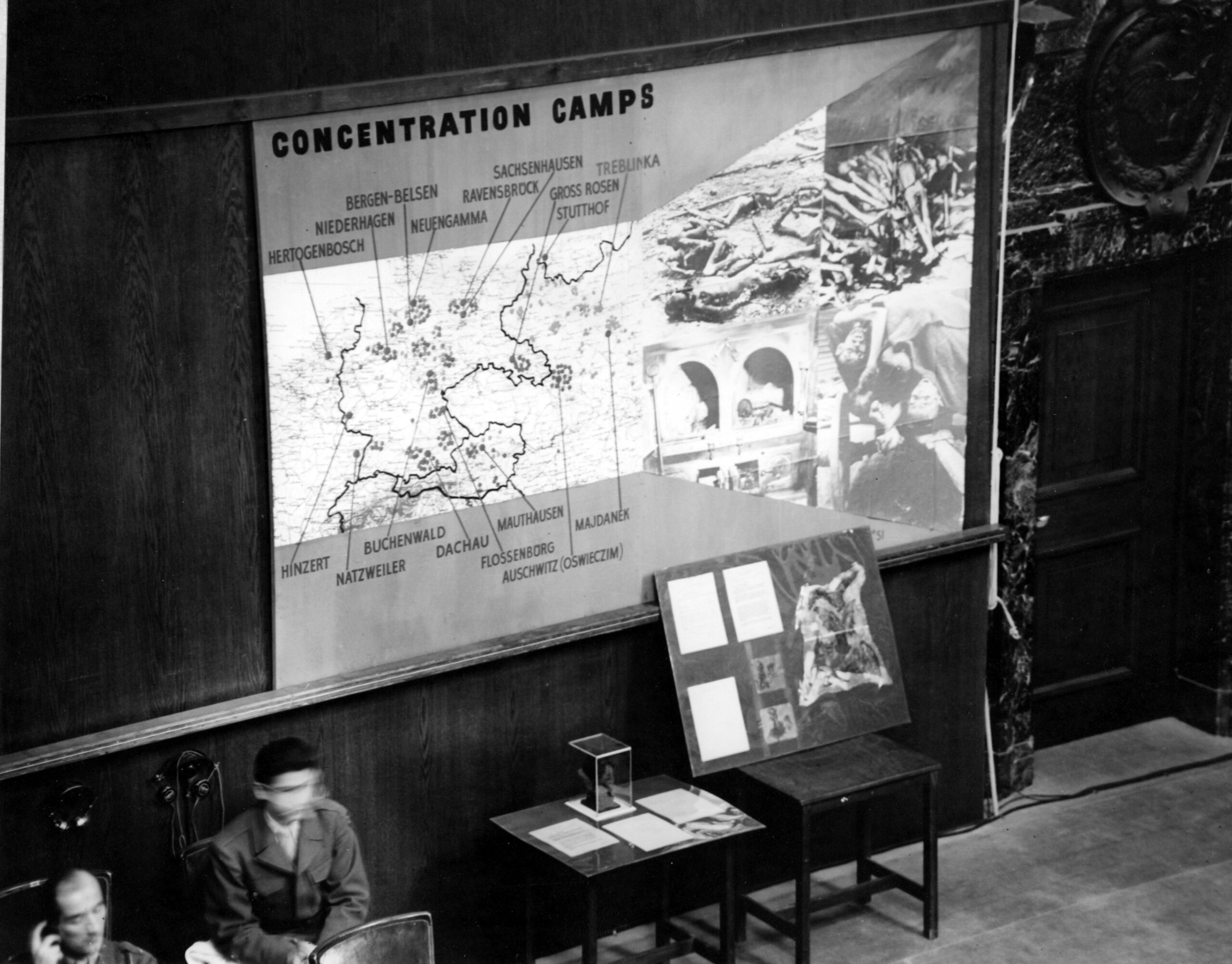

In November 1945, just beyond the walls of a bombed-out city in Germany, justice took the world’s stage. Twenty-one high-ranking Nazi officials sat in the dock at the Palace of Justice in Nuremberg, the first time in history that international law was used to hold leaders accountable for crimes against humanity, crimes against peace, and war crimes. The Nuremberg Trials were not just about accountability for those responsible for World War II and the Holocaust. They were about defining the rule of law in a world that had witnessed unprecedented atrocity.

When the Allied powers agreed to put Nazi leaders on trial at Nuremberg, it was a radical experiment. There had never been an international court, no precedent for prosecuting leaders of a nation for the atrocities undertaken during their reign. U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson, appointed as U.S Chief of Counsel, saw the trial as a moral test for civilization: could the law deliver justice, not vengeance? The processes, procedures, and public opinion were key factors in whether this experiment could take root and be a deterrent. In his opening statement, Jackson spoke words that still resonate today:

Jackson and his international colleagues, from Great Britain, France, and the Soviet Union, sought to demonstrate that justice and the legal process could expose the truth and that leaders of a country, not just governments, could be held responsible for crimes committed during war.

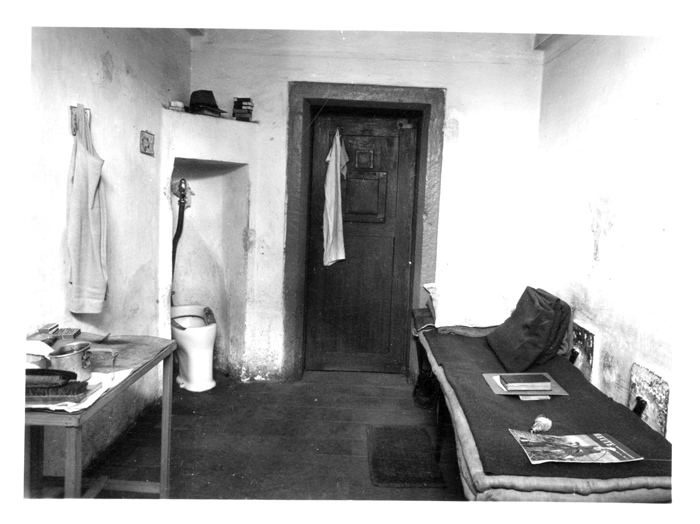

The defendants included Hermann Göring, Rudolf Hess, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Albert Speer, Julius Streicher, and more. Each one of them faced evidence gathered from Nazi records, films, photographs, and eyewitnesses. Each was also interviewed by a United States Army psychiatrist to ensure they were mentally fit for trial. As the defendants were brought to Nuremberg, the United States assigned Douglas Kelley to serve as their psychiatrist. Kelley approached his task scientifically, with a working hypothesis that the brains of the defendants, the men who led and directed the Nazi regime, would be different from the general public. He administered IQ tests, Rorschach inkblots, and lengthy interviews.

Göring, intelligent and vain, sparred with Kelley in long conversations about politics, morality, and power. Almost certainly, Göring manipulated Kelley as Kelley’s observations, later published in his book 22 Cells in Nuremberg, described Göring as a proud, articulate, rational man. Göring bragged about rebuilding the Luftwaffe, defended Hitler’s decisions, and dismissed the suffering of millions. Yet he was also capable of charisma and humor. The contrast fascinated and horrified Kelley equally.

Over the course of 218 trial days, the court examined thousands of documents, maps, photographs, and artifacts, but when the prosecutors showed films from the liberated camps, silence filled the courtroom. As the footage showed corpses and the truth about the Holocaust, even several of the defendants visibly recoiled.

One concern the prosecution had was that many defendants spoke English. Without simultaneous translation, questions were passed through four languages, giving the accused too much time to plan their answers. The system not only improved efficiency but also strengthened the integrity of testimony. Thus, the Nuremberg courtroom became a testing ground for a new technology: simultaneous translation. This system, developed by IBM, allowed the trial to proceed in English, French, Russian, and German, the first time in history that a courtroom used real-time multilingual interpretation.

Cross-examining the defendants was a challenge at Nuremberg. Unlike in American courts, where witnesses swear an oath and face perjury charges for lying, the Tribunal followed procedures closer to European civil law traditions. Defendants could make lengthy statements without the same constraints, often using their time on the stand to justify or reframe their actions.

This was not what Robert H. Jackson was used to. Prosecutors feared the defendants might use the courtroom and media coverage to reach sympathizers. Still, the judges ruled that the accused had a right to speak in their own defense, even if the prosecution objected.

In March 1946, Jackson cross-examined Göring over several days. Frustrated by Göring’s evasive answers and rhetorical flair, Jackson repeatedly appealed to the judges for restraint, receiving little more than sympathy. Recordings from the trial capture Jackson’s irritation as Göring dodged question after question. When British prosecutor Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe took over, he fared somewhat better, having learned from Jackson’s earlier exchanges.

In October 1946, twelve men were sentenced to death, three to life in prison, four to terms of 10 to 20 years, and three were acquitted. Göring, among those sentenced to hang, requested execution by firing squad, believing it a more honorable death for a soldier. The request was denied. Just hours before his scheduled execution, Göring committed suicide using a smuggled cyanide capsule.

The new film Nuremberg (2025), starring Remi Malek as Douglas Kelley, Russell Crowe as Hermann Göring, and Michael Shannon as Robert H. Jackson, dramatizes a story that remains impossible to tell completely or correctly in two and a half hours. We are not here to review films; we leave that up to film critics and film experts. We are holding a screening of the movie with the author of the book that inspired it in January (more info here).

Overall, we, here at the Robert H. Jackson Center, want to give you insight into the full story of what happened in that courtroom and why it still matters.

Jackson saw Nuremberg as a test of the world’s conscience. He believed the trial’s legacy would not only be measured by what it said about the defeated Nazis, but by whether the victors would hold themselves to the same standard of justice as well, saying:

At the Robert H. Jackson Center, we preserve this history not as a closed chapter, but as a living conversation as we continue to explore the questions asked at Nuremberg through education, conversation, and reflection so that Nuremberg remains not only a place in history, but a guide for the future. Beginning in November 2025, we are commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Nuremberg Trials with an International Symposium. Learn more at: Nuremberg Symposium

Eighty years later, the questions raised in Nuremberg continue to echo today: Can law restrain power? Can reason overcome hatred? What makes ordinary people complicit in extraordinary crimes?

For Robert H. Jackson, the Trials were not the end of justice, but the beginning. Nuremberg redefined, some might say established, accountability, especially in times of war. It declared that following orders was no defense for atrocities and that those who issued the orders were not insulated from justice. It affirmed that moral responsibility is individual, even within a regime of terror. And it laid the groundwork for future tribunals, from the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and Sierra Leone to the International Criminal Court in The Hague.