When the International Military Tribunal opened in November 1945, Robert H. Jackson knew that the world was watching. As Chief U.S. Prosecutor, he had argued that the Allies must “stay the hand of vengeance” and demonstrate that law could answer the crimes of the Third Reich.

But there was one defendant who threatened that vision more than any other: Hermann Göring, commander of the Luftwaffe, a master of propaganda, manipulation, and courtroom theatrics.

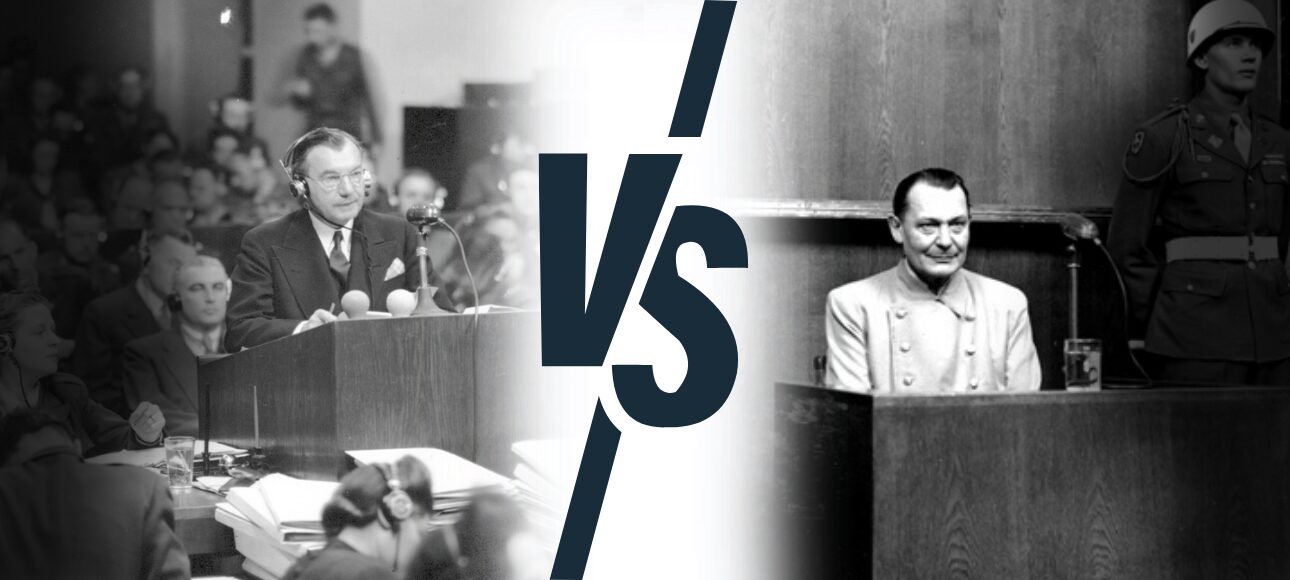

And in late March 1946, Jackson stepped up to the podium to cross-examine him. What followed became one of the most famous and misunderstood moments of the Nuremberg Trials.

Jackson’s cross-examination wasn’t simply about exposing wrongdoing. The prosecution had mountains of documents for that.

Could the rule of law withstand a master demagogue? Could Nuremberg avoid becoming a stage for Nazi revisionism.

Göring intended to turn the trial into a political rally. Jackson intended to turn it into a judicial reckoning. Both men knew the world was listening.

The public often remembers that Göring “got the better of Jackson” in the cross-examination. And in a narrow, procedural sense, that’s true. Göring was a skilled manipulator; for years, he had controlled Nazi meetings with theatrical displays, evasiveness, and bluster.

At Nuremberg, he used the same tactics: Long speeches instead of direct answers, appeals to German nationalism, attempts to incite other defendants, and grand declarations of loyalty to Hitler.

Jackson, trained in American trial practice, expected short answers, clear admissions, and a cooperative judge. Instead, he encountered a defendant who treated every question as an opportunity to lecture, and a tribunal that permitted longer responses than U.S. courts typically allow.

Göring was turning the trial into his stage.

What makes this moment so important is not that Göring landed blows. It’s that Jackson adapted. He shifted strategies, a hallmark of great prosecutors.

He abandoned open-ended questions so that Göring couldn’t riff if the answer had to be “yes” or “no.” He tied Göring down with documents. Captured Nazi orders, minutes from conferences, and memos that undermined Göring’s sweeping statements. He reduced the theatrics by reducing the oxygen. No more speeches. No more baiting. Jackson stripped the interaction down to facts.

It was a strategic retreat in style, but a strategic victory in substance. It demonstrated Jackson’s willingness to learn in real time, in front of the world. It provided a roadmap for the other prosecutors to follow.

The turning point came when Jackson pinned Göring on the Nazi plan to eliminate opposition. Jackson produced documents showing coordinated efforts to crush political parties and consolidate power through violence.

Göring tried to minimize the suppression of political opposition, portraying it as a set of “necessary measures” any strong government would take to maintain order.

Jackson responded by pulling out the very meeting notes where Göring had personally ordered the suppression. With the documents laid bare, Göring had no escape route. His long monologues could not undo his own signatures. It was Jackson demonstrating that, in a courtroom built on evidence, facts outlasted theatrics.

The cross-examination became, in many ways, a story about learning. Jackson had been a country lawyer, prosecuted corporate fraud, argued before the Supreme Court, and served as U.S. Attorney General. But in Nuremberg, he faced a defendant unlike any he had encountered. The ability to pivot, to rethink strategy under pressure, showed intellectual humility and professional discipline.

Göring gained the most traction when the exchange resembled a political argument. When Jackson turned to structure, documents, and narrow questions, Göring lost his platform.

Nuremberg wasn’t an American courtroom. It was a hybrid tribunal, with different rhythms and rules. Jackson used the Göring episode to recalibrate and lead the prosecution more effectively going forward.

In the end, the evidence ultimately won the day. The transcript reveals that Göring’s most “impressive” moments were bluster. The damning moments were documentary. In legal education today, this episode is often used to show that a cross-examination isn’t a debate; it’s a guided tour using the witness’s own record.

Jackson’s exchange with Göring continues to resonate because it teaches a timeless lesson: justice isn’t measured by whether the prosecutor “beats” a witness in a verbal duel. It’s measured by whether the truth emerges.

And in that sense, Jackson’s cross-examination succeeded profoundly. Göring’s own words, captured, cataloged, and confronted, became some of the most powerful evidence of the Nazi leadership’s intent, planning, and crimes. Jackson ensured that history would not rely on speeches alone, but on verified documents.

Today, lawyers studying Nuremberg point to Jackson’s approach not as a flawless performance, but as a class in adaptation, humility, and fidelity to truth.

His cross-examination of Hermann Göring was messy, human, but ultimately successful, albeit not in that theatrical way we would all love to see.