On September 2, 1940, President Franklin D. Roosevelt announced a landmark agreement between the United States and Great Britain that would come to be known as the Destroyers for Bases Agreement. At a time when Nazi Germany threatened Britain’s survival, this deal symbolized America’s growing role as the “Arsenal of Democracy” and a turning point in U.S. foreign policy before its entry into World War II.

Attorney General’s Legal Opinion (August 27, 1940):

- Before the agreement could move forward, President Roosevelt asked Jackson whether he had the legal authority to transfer U.S. destroyers to Britain without congressional approval. Jackson issued a formal Attorney General’s opinion, concluding that the President did indeed have such authority.

Key Legal Reasoning:

- Presidential Power as Commander in Chief: Jackson argued that the President, as Commander in Chief, had broad discretion to dispose of military property no longer deemed essential for U.S. defense.

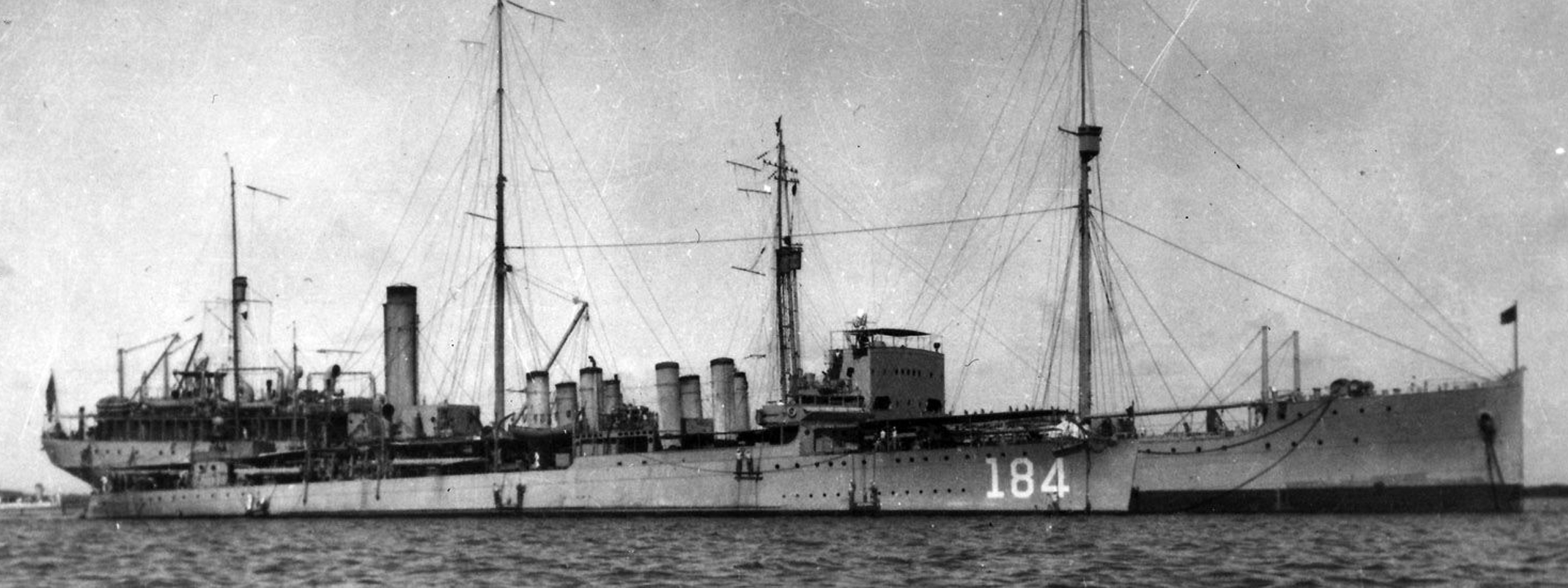

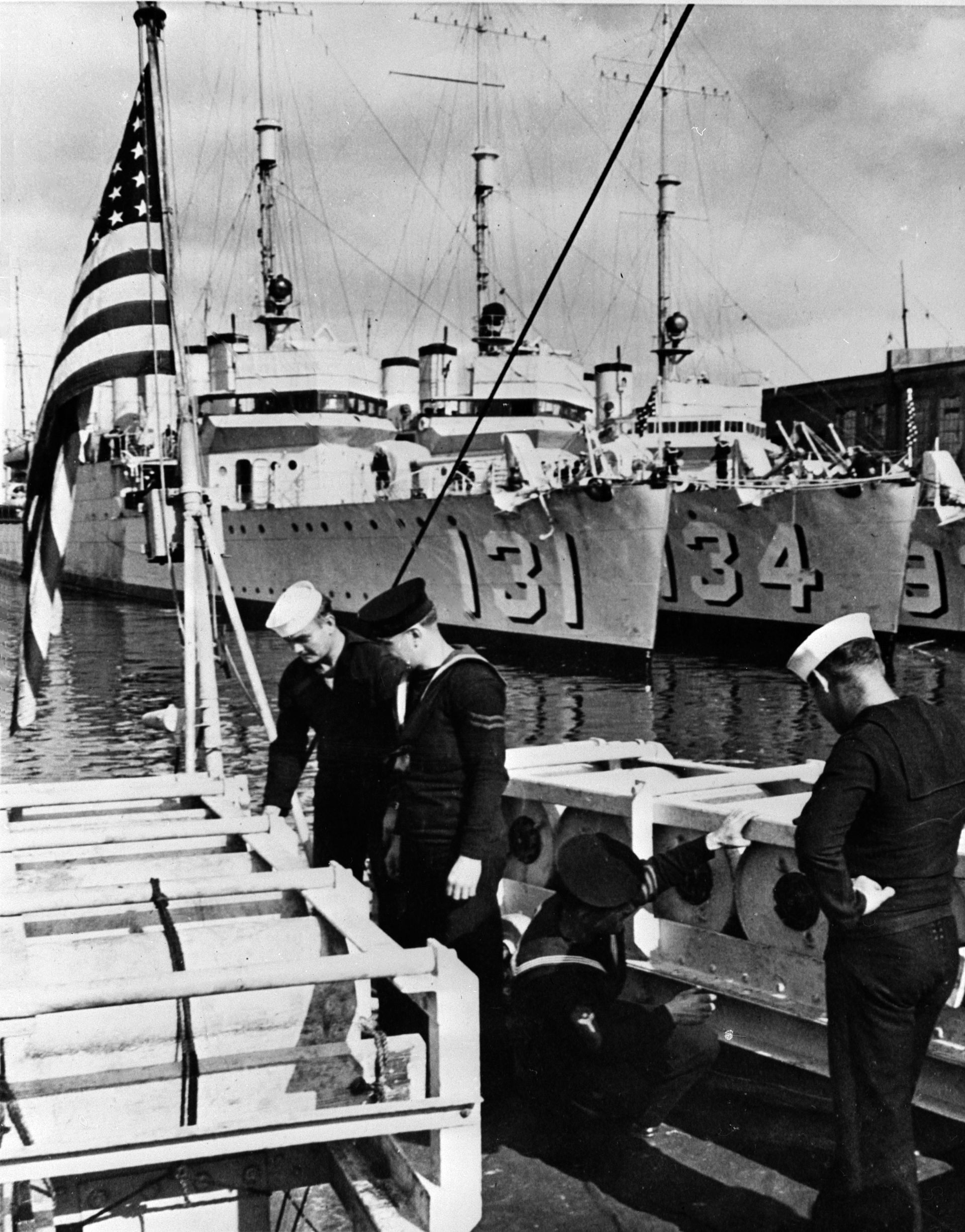

- Obsolete Destroyers: The ships in question were older “flush-deck” destroyers from World War I, considered outdated by U.S. Navy standards. Declaring them “not essential,” Jackson reasoned, made their transfer permissible.

- Executive Agreement, Not a Treaty: Jackson defended Roosevelt’s decision to structure the deal as an executive agreement rather than a treaty requiring Senate ratification. He maintained that the President had independent constitutional authority to make such agreements for national security.

Impact of Jackson’s Opinion:

- Jackson’s reasoning gave Roosevelt the legal and political cover he needed to proceed swiftly. Without it, critics might have successfully blocked the deal as unconstitutional. His opinion helped expand the understanding of executive power in foreign affairs—a theme that would continue throughout Jackson’s career on the Supreme Court.

- The Destroyers for Bases Agreement became one of the most cited examples of executive power in foreign policy.

- Jackson’s opinion foreshadowed his later, more famous writings on executive power, especially his concurring opinion in Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer (1952), where he outlined the enduring framework for evaluating presidential authority.